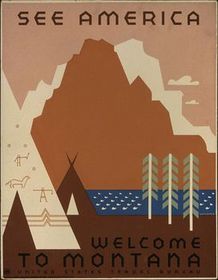

WPA Artist, New York Poster Division

by Nettie Roth

Jerome Henry Roth, who passed away in 2008 at the age of 90, started painting in elementary school. On graduating from James Monroe High School in the Bronx, he was awarded a scholarship tot he Art Students League. He went on to graduate from Pratt Institute while working as the youngest member of the poster division of the WPA (Works Progress Administration of the Great Depression). As the 16-year-old who talked his way into being taken on as a full-fledged artist, he was mentored by Bauhaus-trained project supervisor Richard Floethe. Under Floethe's mentoring he designed posters for the U.S. Tourist Bureau, Orson Welles Theatre, concerts and the U.S. Department of Health. He painted in oils, watercolor and gouache during this period, as well as doing whimsical line drawings.

Following the WPA, Roth sought employment in the private sector and was hired as graphic assistant to well known designer Herbert Bayer. He later worked at Warner Brothers, producing posters and souvenir books for movies, including Yankee Doodle Dandy.

During World War II Roth volunteered with the U.S. Army Air Corps and flew 30 missions over Germany as the lead bombardier-navigator-radar (code-named "Mickey"). He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

After returning from the war, Roth resumed drawing and painting. His paintings have been shown extensively over the years with one-man shows at Andrea Marquit Fine Arts Boston, MA; Garrison Art Center, Garrison, NY; Overseas Press Club, New York City; Nardin Fine Art, Cross River, NY, and Modernism Gallery, Coral Gables, FL. He participated in numerous group shows including Susan Teller Gallery, Salmagundi Club and Kaufman Art Gallery, New York City; as well as Silvermine Guild, New Canaan, CT; and Garrison Art Center, Garrison, NY.

Jerome Henry Roth, who passed away in 2008 at the age of 90, started painting in elementary school. On graduating from James Monroe High School in the Bronx, he was awarded a scholarship tot he Art Students League. He went on to graduate from Pratt Institute while working as the youngest member of the poster division of the WPA (Works Progress Administration of the Great Depression). As the 16-year-old who talked his way into being taken on as a full-fledged artist, he was mentored by Bauhaus-trained project supervisor Richard Floethe. Under Floethe's mentoring he designed posters for the U.S. Tourist Bureau, Orson Welles Theatre, concerts and the U.S. Department of Health. He painted in oils, watercolor and gouache during this period, as well as doing whimsical line drawings.

Following the WPA, Roth sought employment in the private sector and was hired as graphic assistant to well known designer Herbert Bayer. He later worked at Warner Brothers, producing posters and souvenir books for movies, including Yankee Doodle Dandy.

During World War II Roth volunteered with the U.S. Army Air Corps and flew 30 missions over Germany as the lead bombardier-navigator-radar (code-named "Mickey"). He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

After returning from the war, Roth resumed drawing and painting. His paintings have been shown extensively over the years with one-man shows at Andrea Marquit Fine Arts Boston, MA; Garrison Art Center, Garrison, NY; Overseas Press Club, New York City; Nardin Fine Art, Cross River, NY, and Modernism Gallery, Coral Gables, FL. He participated in numerous group shows including Susan Teller Gallery, Salmagundi Club and Kaufman Art Gallery, New York City; as well as Silvermine Guild, New Canaan, CT; and Garrison Art Center, Garrison, NY.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed